When a child activist receives death threats

Colombia’s complex and deadly battle for environmental progress | By Inigo Alexander

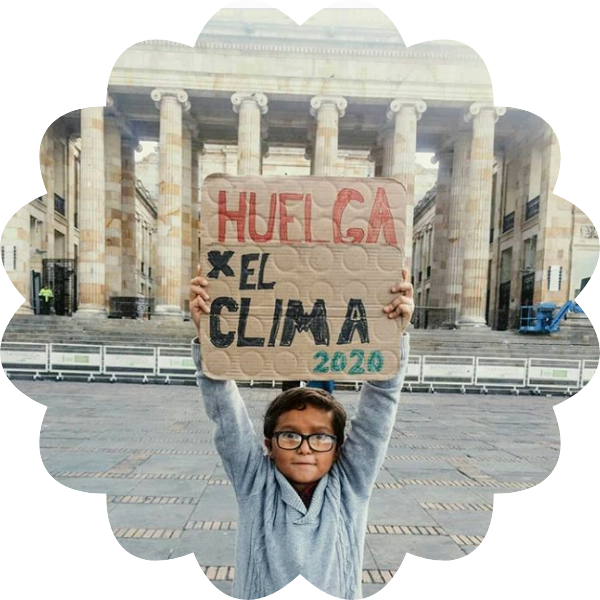

On December 18th 2019, a person of small size but large character made an unusual appearance in Colombia’s National Congress. It wasn't a politician, a diplomat or an international guest, but an eight-year-old climate activist by the name of Francisco Vera.

Well-spoken and sharply dressed, Vera urged politicians to implement more efficient environmental policies. His speech quickly went viral, bringing environmental concerns to the fore of Colombian politics—truly uncharted territory.

Earlier in 2019, Vera had founded the organisation Guardianes De La Vida alongside six school friends. The small group of children would meander through their hometown of Villeta picking up rubbish and chanting about climate change along their way.

However, in late January of this year, Vera received a grim accolade, a death threat. The 11-year-old received messages threatening to “cut his fingers off” and “skin him” after posting a video demanding greater government support for Colombian children undergoing online schooling as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The threats sparked national outrage in Colombia and shed light on an issue that Colombia is struggling to keep at bay: the attacks towards social and environmental activists across the country.

“When you become a public figure you become a target for attacks, like Francisco. But the more visible one is, the less likely they are to get killed. It ends up shielding you in a way,” says Robinson Duarte, a political activist and a member of the green party Alianza Verde.

A rise in killings

In 2019 Colombia saw the highest number of murdered environmental defenders in the world, a record 64 deaths, according to the human rights organisation Global Witness.

The latest figures from Colombia’s Institute for Development and Peace Studies paint an equally grim picture for other activists in the country, with 284 social activists and human rights defenders murdered there last year.

Violence against activists is used as a means of deterring a movement and establishing boundaries between the hopeful and the lawless.

Green activists seeking to raise awareness on land use for illegal crop growth, detrimental mining projects or defend indigenous land often step on the toes of criminal gangs operating in those areas. Close encounters with the criminal underworld are an unfortunate reality for those speaking out in Colombia, and it is this that often triggers the attacks and killings.

"If they kill an environmental defender it instills fear into people and deters them from mobilising, also because they understand there is structural complicity," says Duarte. “The state does not respond to the defense of human rights nor the defence of social activists."

According to a report from the UN Human Rights Council, almost 90% of murders of human rights defenders do not result in a conviction. Despite Colombian President Ivan Duque vowing to capture the “bandits” behind Vera’s death threat, a police investigation is still ongoing.

“Killing a social leader has become a solution to a problem, it guarantees visibility and creates a gigantic setback for the fight to defend the environment" - Robinson Duarte

“Violence is a clearly visible issue, it’s witnessed and gets denounced but there is no response from the state. If there’s no response the perpetrators feel that they can get away with it because nothing will happen to them,” says Laura Furones, advisor for Global Witness’ land and environmental defenders campaign.

“The data we release is necessarily conservative. Firstly because we only account for assassinations, and secondly because there are lots more cases that the press don’t hear about or we aren’t able to verify enough to include. Our data is already extremely worrying and it’s still based on conservative calculations,” adds Furones.

Issues unresolved by previous Peace Accords

Following the 2016 Peace Agreements between the Colombian government and the guerilla group FARC, many Colombians hoped internal violence would dissipate. This has not been the case.

Organised criminal and paramilitary groups have stepped into FARC’s vacant shoes and have become responsible for many of the killings amongst the country’s activists, environmental or otherwise. Global Witness found that almost a third of deaths among environmental activists in 2019 were due to paramilitary groups.

The interconnectedness of land use, crime and environmentalism in Colombia means that activists and paramilitary groups operate within the same regions, with entirely contrasting goals.

The United Nations Human Rights Office found that the volatile power dynamics and ongoing violence have also been fostered by turbulent illicit crop substitution programmes, land restitution and rural reform, as well as difficulty dissolving armed criminal groups.

The Peace Agreements sought to reduce many farmers’ dependence on illicit coca cultivation in hopes of hindering the drug trade that relied on it and caused ongoing violence. Farmers were offered incentives to replace their coca harvests with the likes of coffee and cacao crops, but many of those who participated in the programme were met with intimidation, threats and violence on behalf of paramilitary groups still reliant on illicit cocaine production.

“Since the Peace Agreements the situation has gotten extremely complicated and a lot of the crime in Colombia is related to illicit crops. It’s generating a large amount of conflict because it’s a cause of tension between the communities that are trying to change lifestyles and do away with illicit crops in a context where drug traffickers continue to reign,” Furones explains.

Despite the continued violence and threats, Colombia’s environmental movement is slowly making inroads thanks to people like Vera. Environmental issues are slowly seeping into the national psyche, though Juan José Guzman, an associate for sustainable finance and fiscal policy at the Colombian think-tank Transforma, acknowledges it is an uphill struggle.

“Environmentalism is currently in a complicated state,” he says. “Nowadays climate change is perceived more as an existential crisis, it’s not so much a moral or ethical debate as it was in the past but instead is a question of survival. In Colombia, unfortunately, that desire to survive is not only based on how to survive an environmental and economic crisis, but also wanting to survive threats and attacks.”

The Government’s Green Growth

The Colombian government noticed the movement’s growth in importance and acted accordingly. In 2020 the country rose nine spots to 25th in the World Economic Forum’s Energy Transition Index, with Uruguay being the only other Latin American country ahead of them. In December 2020, 80% of the country’s power was produced by renewable sources.

"In Colombia the number one driver of climate change is not energy generation, but land use and deforestation” - Juan José Guzman

The country is set to increase its renewable energy production 50-fold by 2022, pumping $37 billion pesos into the industry in hopes of creating 56,000 new jobs. According to government data the State currently has 32 ‘clean development’ projects in place with total funding of $19.2 billion pesos for projects on sustainable agriculture and renewable energy.

Additionally, a new wetland protection programme was also introduced in January, a green bond investment programme was established to fund environmentally friendly projects across the country, and Congress recently approved legislation aimed at tackling the use of single-use plastics and improving the national recycling infrastructure.

Nonetheless, despite the government’s efforts, Guzmán believes Colombia is still falling short of the mark. When asked whether he believed the government’s policies to be efficient or not, he had a clear response.

“No, not at all. I’d say the last two administrations have taken the initiative simply because it’s the current political trend internationally. Colombia has been an extremely shy country in this regard. When you begin to look at the laws and the different government programs, you see a timid approach to the subject. It’s a bit absurd that you have the president talking about renewable energy when in Colombia the number one driver of climate change is not energy generation, but land use and deforestation,” he says.

In order to move forward, Guzmán believes that Colombia should “stop emulating Europeans and North Americans and believe that is the way to solve things,” and urges the state to take a more independent approach that caters to Colombia’s specific environmental needs. (Government representatives from the Department of National Planning were approached for comment but none were available.)

The threats directed towards young Vera have forced Colombia to grapple with its understanding of environmentalism, Many hope this will be the wake-up call that leads to more effective legislation, protection and support.

As Laura Furones puts it, the government "must not tolerate this type of behaviour and intimidation and protect them before anything happens, and if something does happen they must ensure that the perpetrators do not go unpunished."

Article written by Inigo Alexander (@Inigo_Alexander)

Headline image from Francisco's public Facebook account (link)

Please consider supporting our journalism: https://www.paypal.com/donate?hosted_button_id=FFQ2VNZ6Z6BYG